Grief and the Regency

/"Grief and the Regency" doesn't have quite the same appeal as "Sex and the City," but bear with me. I have tried to write this blog post for six months. Perhaps I should have let it go. And yet every time I opened Wordpress, I couldn't ignore the draft and move on - or force myself to write it. In April, one of my friends died suddenly of a pulmonary embolism. He wasn't quite thirty. I had dinner with him and his fiancee the previous week, and he seemed fine - happy with life, excited about the wedding, eager for the next step. A week later, I was sitting in his fiancee's parents' living room, crying with her and mourning what was supposed to have been. Their save-the-date cards had been delivered the day he died.

The mourning process is something I've thought a lot about over the past few months. I'm much closer to the fiancee than I was to him; she and I have been friends and coworkers for years, although I worked with him as well. They were wonderful both together and apart, and I loved hanging out with them as a couple even though I didn't have someone by my side to make it a double date. I was devastated for her...am still devastated for her...was supposed to have attended their wedding last weekend, and instead saw a string of tributes posted on the Facebook page created in his memory.

The point of this post isn't to bring you down, or to make me feel better - it's not your issue, and I don't believe that "blog posts heal all wounds" is a valid statement. But in my ruminations on grief, I've wondered whether the very strict rules around women and mourning during the Regency and Victorian periods were to save other people from having to deal with the bereaved. Reaching out to someone like my friend is hard - does she want to talk? Is she overwhelmed with people? Is she trying to move on? There's the fear of not knowing what to say, of saying the wrong thing, of bringing up a bad memory, of causing unintentional pain.

Middle and upper class Regency/Victorian ladies didn't face that pressure to the same degree. The funeral was held, the house and the ladies were draped in black, and the ladies weren't seen again at major social functions until their prescribed mourning time was up. By then, if they hadn't moved on, Society certainly had. One lovely (from a writing standpoint, not an emotional standpoint) example of this was in Deanna Raybourn's first Julia Grey novel, Silent in the Grave - a whole year of mourning passed by very quickly, with Julia essentially a bored, aimless prisoner in her own house. Almost certainly worse for *her* than being able to go out, socialize, take her mind off of her loss - but also almost certainly easier for those who didn't want to be reminded of her grief.

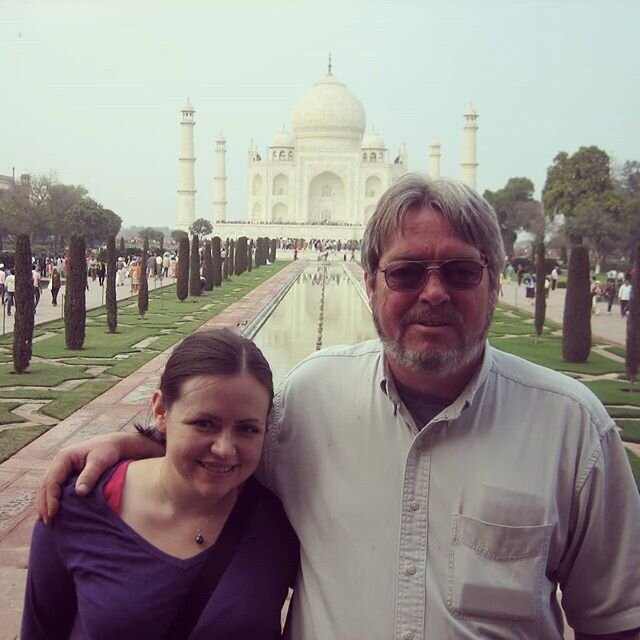

There's a long history of the bereaved (and by that I mean almost entirely women - men were expected to move on) being ignored or tossed aside, from the very word 'relic' (a rather disagreeable word for a 'widow') to the act of sati (Indian widows immolating themselves on the pyres of their husbands, either voluntarily or under duress). I think we can all be thankful that sati is no longer common - in fact, it's illegal to even see sati committed in India, in an effort to prevent forced immolation. And we no longer expect widows to sit at home alone, wearing black and staying out of the way as others go about their lives.

But rituals, whether it's weddings, funerals, christenings, handfastings, religious events, maypole dances, or any other events, give people a list of rules to follow. They reduce the outward side of something like mourning to a checklist: dye clothes black; cover the mirrors with black cloth; muffle the door knockers; stop the clocks. I don't want to be told how to mourn, just as I wouldn't want to be told that my wedding has to follow an exact plan, or that my funeral can't be light on hymns and heavy on Bon Jovi (just kidding about that, I think). And yet...

...and yet, checklists make it all easier. Perhaps there wouldn't be $100,000 weddings if they were still supposed to take place before noon in one's own parish. Perhaps my neighbors would have greeted me with casseroles when I moved in a few months ago, rather than remaining strangers and leaving me wondering if I'm letting in a resident or a serial killer when I hold the gate for the person following me. And perhaps I would know what to say to my friend, how to comfort her, and how to comfort myself.

No checklist will solve that. But what do you think? Do you wish your community had more rituals than it currently does? Are things still too ritualized for your liking? Or are you the proverbial Baby Bear of rituals and have managed to get it just right?