There, but for the grace of God...

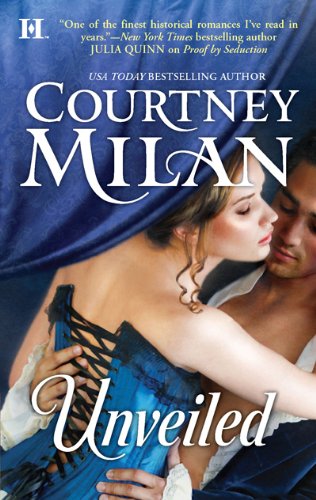

/ One of the authors I follow on Twitter is Courtney Milan, who has released a series of excellent historicals over the past year and has another book, UNVEILED, coming out in January. If the cover alone wasn't enough to seduce me, I'm quite intrigued by the premise - the hero has just found information to get the heroine (and her brothers) declared illegitimate, which means that he will inherit their father's dukedom while the duke's kids will be cast out of society. But, as these things happen, the hero and heroine meet and fall in love despite all that.

Sounds lovely, right? So I was quite saddened for Ms. Milan when my Twitter feed gave me all the details of a review for her book that went horribly awry.

One of the authors I follow on Twitter is Courtney Milan, who has released a series of excellent historicals over the past year and has another book, UNVEILED, coming out in January. If the cover alone wasn't enough to seduce me, I'm quite intrigued by the premise - the hero has just found information to get the heroine (and her brothers) declared illegitimate, which means that he will inherit their father's dukedom while the duke's kids will be cast out of society. But, as these things happen, the hero and heroine meet and fall in love despite all that.

Sounds lovely, right? So I was quite saddened for Ms. Milan when my Twitter feed gave me all the details of a review for her book that went horribly awry.

Basically, Publishers Weekly's review (scroll to the middle of the page) of UNVEILED proclaimed "the love story...genuinely satisfying and Margaret's dilemma movingly portrayed", which is a v. good thing. But, the reviewer also said "the conflict [is] dependent on the unlikely scenario of Parliament legitimizing a bigamist's bastards, fatally marring an otherwise promising novel."

Daggers, right? That's the kind of review that kills a little bit of a writer's soul, or at least I imagine it is - particularly writers who really, truly care about and strive for historical accuracy. And Ms. Milan does care about accuracy; while she didn't respond to the review directly, she did a very calm, thorough post about the historical research that went into her plot, and there really was a case in Britain in which a family under similar circumstances was legitimized by an Act of Parliament. As a result of the tempest in the Twitter teakettle over this, PW did revise the review slightly to say "unlikely scenario" (before, I believe it said something more along the lines of "impossible", but don't quote me), but the review still stings.

Now, I don't know Ms. Milan (although I have won two different books from her on Twitter, so I suppose I'm biased towards thinking she's a v. nice person), I don't know the reviewer, and I don't know the deep intricacies of English inheritance law. But the hard thing about writing historical romances is that there is a divide between "history" (i.e. what really, factually happened) and "romance history" (i.e. what is commonly accepted as fact in the world that Smart Bitches/Trashy Books would call "Romancelandia"). As a minor example, in Romancelandia, the waltz is danced in nearly every London-based Regency romance -- but in the real world, everything I've read indicates that it wasn't danced until at least 1813, and didn't get a broader blessing until 1816 or later.

So the readership and the reviewers have what they consider a very clear sense of what "Regency" (or, in Ms. Milan's case, Victorian) is, and writers who stray away from Romancelandia into the "real world" are treading a very narrow line. And I must admit that before this brouhaha, I would have also said that the plot sounded unlikely - I'm part of the Beau Monde online special-interest chapter of RWA geared toward the Regency, and the fact that bastards cannot and will never inherit has been rehashed in that group many times. But, the legal case that Ms. Milan found has never come up there either, and I believe her now that I've seen it.

But as an author, how do you handle these questions of historical accuracy? As a reader, can you trust that the author has done their research, or do you throw the book against the wall when it violates the precepts of Romancelandia? As editors and agents continue to look for new and fresh stories, writers must go farther afield in search of inspiration - and what they bring back, while based in fact, may not meet the sniff test for those who believe that Romancelandia's Regency period and the real Regency are the same thing.

Ms. Milan said that perhaps an author's note explaining her research might have helped; perhaps that really is the only way to win over the disbelieving reviewer. It's certainly something I will consider if I publish a story that doesn't match readers' understanding of the period - after all, if I felt major sympathy pangs for the author after reading the review, I can't imagine how it would feel to be the direct recipient of that kind of unfounded criticism.

But what do you think? Are most readers more forgiving than the reviewer was? Or is an author's note the only way to deal with this?